Today I am profiling Valterra Platinum, the world’s largest miner of platinum group metals, or PGMs.

Our story begins with Barney Barnato, a British contemporary of and rival to Cecil Rhodes, who arrived in what was then known as Cape Colony in 1873, during South Africa’s ‘diamond rush’. He had huge success and ended up owning 25% of De Beers diamond mines alongside Rhodes. He later consolidated his holdings in diamond and gold mining into Johannesburg Consolidated Industries (JCI), before losing his fortune in a stock market rout of 1896.

Barnato died soon after, falling overboard in an unsolved suicide/ murder, but JCI lived on and was able to capitalize when large platinum deposits were discovered in South Africa in 1924. The boom proved short-lived and in the Great Depression of the 1930s the entire South African platinum industry was closed down for 18 months, leading to widescale bankruptcies.

By the 1960s, JCI had grown to be the world’s largest platinum miner. It was then acquired by Anglo American, a conglomerate founded by Jewish German émigré Sir Ernest Oppenheimer (no relation to Robert!). During Apartheid, as global businesses were pressured to exit South Africa and capital was thus scarce, local conglomerates such as Anglo were able to buy up huge swathes of companies on the cheap. By some estimates at the end of Apartheid, Anglo controlled over half of all private industry in the nation. As Nelson Mandela took the presidency in 1994, the country produced well over 80% of the world’s mined platinum.

The Oppenheimers remained major shareholders of Anglo American into the 21st century, making them one of the richest families in the world. With their exit the company became vulnerable to takeover with a number of potential suitors circling in recent years. In 2024, mining giant BHP attempted a hostile takeover. Anglo management were able to swat away the attempt, but one of their concessions was to agree to spin off their diamond mining (De Beers), nickel assets, as well as 79% owned PGM miner Anglo American Platinum (Amplats).

The spin off has just been completed and in the process Amplats has a new name, Valterra Platinum. The company has primary listings in Johannesburg, London, and an ADR.

So what is platinum?

The Egyptians and South Americans used the metal in jewelry thousands of years ago. The Spanish gave it its modern day name when they found deposits in Colombia in the early 1700s. They thought it an inferior version of silver, hence the name platina, the diminutive of plata, the Spanish word for silver.

Platinum is 30 times rarer than gold and has historically traded at a large premium to gold. However, in recent years this has reversed:

Platinum deposits are usually found together with its close relative palladium as well as rarer elements rhodium, ruthenium, iridium and osmium. Collectively they are called platinum group metals or PGMs. The first two are the vast majority of volume mined, although some of the others fetch very high prices (an ounce of rhodium and iridium are more expensive than gold). Last year 30% of Valterra’s sales were platinum, 22% palladium, 20% rhodium, 28% other including ruthenium, nickel, gold and other metals, but this swings around from year to year depending on commodity prices.

Over half of global primary (as opposed to recycled) platinum & palladium production comes from South Africa (80% of platinum) with the remainder concentrated in Russia, Zimbabwe and the US & Canada. Only 4% comes from outside these 5 countries. Recycling is the second largest source of supply after South Africa, at a quarter of total supply.

The primary use for all PGMs is for catalytic converters which are mandated in cars to reduce harmful pollutants in exhaust fumes. A modern ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicle has about 4 grams of PGMs in it, a figure that is going up over time as emissions standards rise. This represents 2/3rds of global PGM demand, with the next largest category jewelry at 8%.

One of the reasons that platinum prices have fallen from their prior peaks in 2008 and again in 2011 of around $2,000 an ounce is a narrative that catalytic converter demand will soon decline towards zero as electric vehicles (EVs) replace polluting combustion engine vehicles.

I am skeptical of this narrative for two reasons. The first is that transitioning quickly to a world where 100% of cars on the road are EVs risks placing enormous strain on supply chains for battery metals (such as lithium and cobalt). Mining these metals can be hugely energy intensive, land intensive (in the case of lithium) and environmentally damaging. And in pure financial terms this transition risks driving metal prices to prohibitive levels. We saw this recently as EVs went from 2% in 2019 to 10% market share by 2022, resulting in lithium prices rising 6-fold, while cobalt doubled. High prices can act as a brake on the EV transition.

We also have to consider that EVs will have to compete for those metals with the vast array of batteries that will be needed to back up intermittent solar and wind generation. Global battery storage investment in 2024 was 126GW, 0.4% of total electricity generation so much more will be needed to support all the renewable capacity being built.

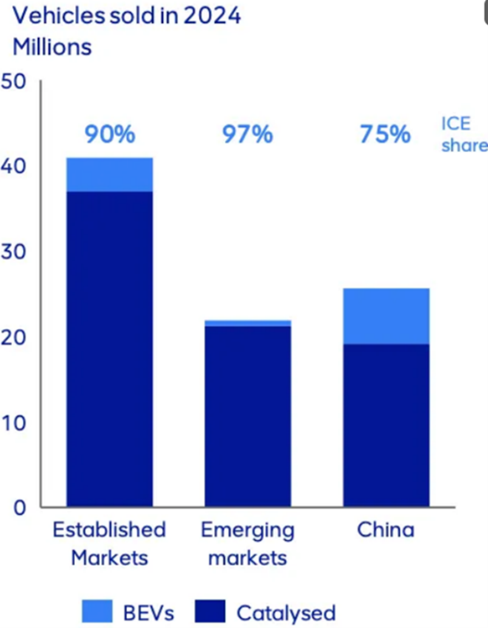

Secondly, narratives tend to be extrapolations from our collective lived experiences. And while most investors sit in the west in very wealthy cities, the vast majority of the population lives in very different circumstances. That’s why I like this chart courtesy of excellent Substack ‘Trader Ferg’ which shows the current state of play:

India, the most populous nation on earth (1.4bn), bought 4m cars in 2024, the same as the UK & Canada combined with their collective 100m population. There is a total stock of 70m cars in India (1 per 20 people), thus Indians are not looking to trade in their gas-powered car and replace them with an EV, they are aspiring to buy a car for the first time, which means gasoline consumption increasing from close to zero, even if many of those first time buyers opt for EVs. Indians bought 105,000 electric cars in 2024, one for every 13k of population.

Here's another chart showing battery EV penetration slowing compared to expectations:

And while EVs grab the headlines, there is another category of vehicle that is quietly guzzling (sorry) market share. The hybrid.

There are two types of hybrid, the type made famous by the Toyota Prius which uses regenerative braking to recharge the battery, as well as plug in hybrids (PHEV ) where as the name suggests you plug the car into a charger much like an EV. The PHEV will use battery power until it runs out, then switching to the gas tank. Both technologies are significantly more fuel efficient than a traditional ICE vehicle.

In the 3 key markets of China, US & EU (collectively over 60% of car sales) hybrids – of both kinds - outsold EVs. And because the chemical reaction they are catalyzing occurs more efficiently at higher temperatures, a hybrid requires more PGMs than an ICE vehicle with its hotter engine.

Not only did hybrids outsell EVs, they grew faster in 2023 & 2024, so their lead is accelerating. This hybrid story is obscured by the fact that many organizations that track data include hybrids in their EV figures.

At the risk of getting sidetracked, I think one trap that environmentalists have fallen into, and increasingly sympathetic politicians as well, is to treat greenhouse gas emissions (principally CO2) as the only constraint we collectively need to work within. The reality is that there are many constraints to consider in managing the complex global economy, principally financial (consumers are unlikely to willingly pay more for an equal or lower quality product), land (technologies like solar are incredibly land intensive), water, and in this case resources such as battery metals.

Hybrid technologies make much more efficient use of battery metals. As Doomberg points out in their fantastic Substack, “the electric Hummer, which sports a massive 200kWh battery. This is an environmental abomination. That same battery pack could support 10 PHEVs and have a far greater impact on reducing our demand for oil,” adding “on a gallon-of-gasoline-abated-per-pound-of-battery basis, PHEVs are far superior to full BEVs [battery electric vehicles].” So I believe customers, auto companies and regulators will increasingly favor hybrids.

It is also worth noting that PGMs play a role in the hydrogen economy, i.e. in electrolysis (blasting electricity into water to separate the H from the O) and then using that hydrogen as a fuel in, among other things, vehicles. These use cases are very small today but could potentially be much larger. I do remember meeting the management team of a platinum miner a decade ago and they had driven a hydrogen powered car to the meeting, so I wouldn’t hold my breath that this is about to go mainstream.

Supply

Ok we’ve covered demand, but the real cyclicality of commodity prices comes from the supply side. Broadly what tends to happen is that a commodity price rises for whatever reason (supply issues, unexpected demand etc). Miners thus enjoy high profits. This incentivizes existing operators and new entrants to expand production. This leads to more supply which leads to lower prices. Miners make less money and many fall into losses, which leads to bankruptcies, less investment, lower production, and voila, higher prices!

The problem is that the time frame from the decision to invest in building a new mine to actual production can be 10 years and longer. And similarly when a mine starts burning cash, it doesn’t get shut down the next day. It costs money to shut down, you have to pay severance to your employees etc, so management teams will often play a game of wait and see, and hope that their competitors blink first. So that is why you have wild oscillations between peaks and troughs.

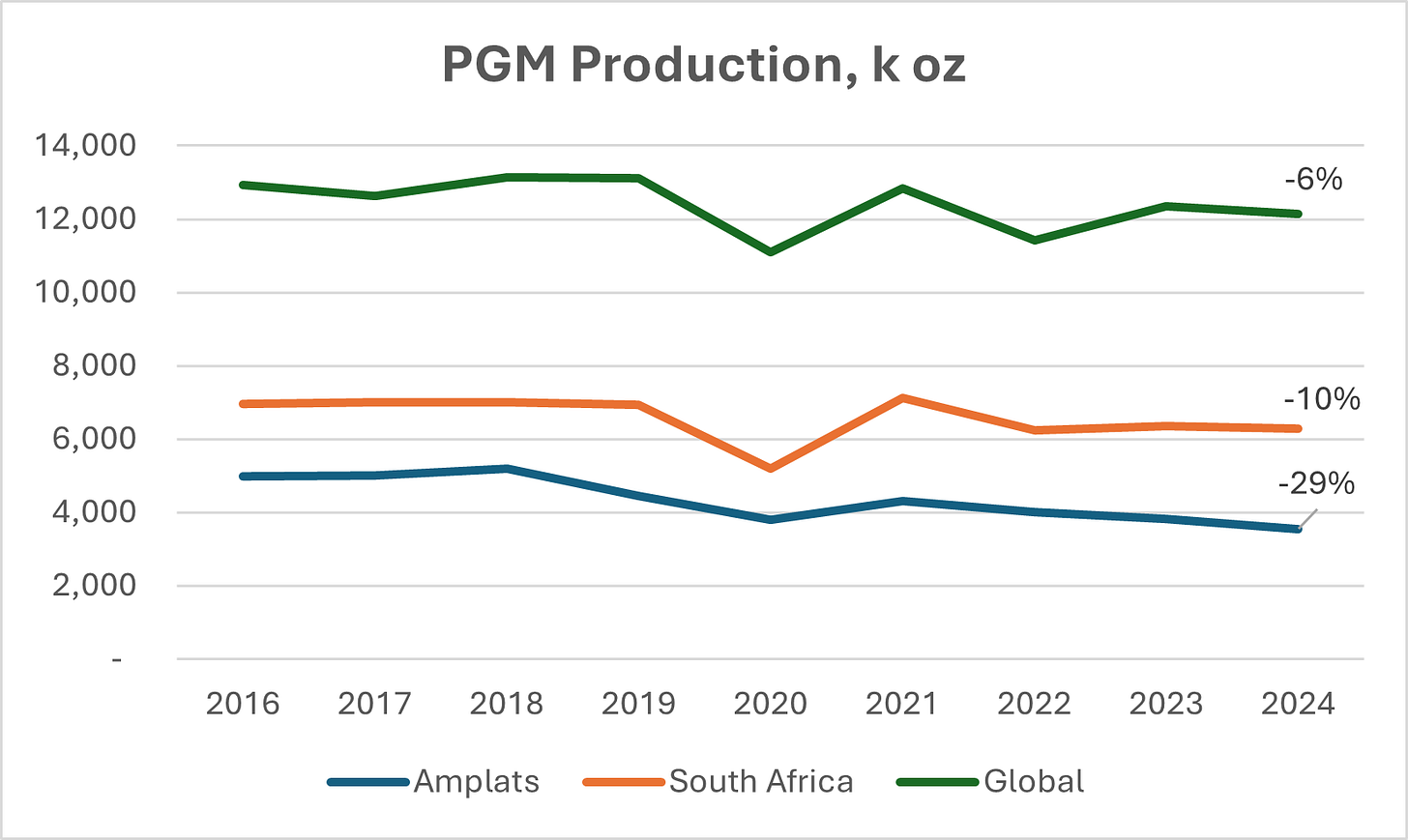

Because most of the world’s PGMs come from just one country and in fact 3 miners, all of them publicly listed, we can see relatively easily what long term supply is likely to be. The three miners (which have some relatively small overseas operations) collectively account for 2/3 of global primary supply.

While investment has picked up from a historic low, it is still way below peak levels of 30% of sales.

Mining is a capital intensive business. A mine depletes over time, and so without continued investment to find and exploit new reserves, production will inevitably fall. Companies have been flagging that production will fall due to mine closures– with Impala even predicting no further mines being built in SA:

The impact on production is already becoming visible, and Valterra projects a further 16% fall in primary production by 2030:

It is worth noting that one reason why Valterra production has fallen more than the industry is that their peers have acquired other miners/ assets, whereas Anglo has been a seller, including a large high cost mine they gave away – for 1 Rand - to Sibanye.

So why Valterra over other miners?

At current market caps you could actually buy virtually the entire platinum mining industry, which supplies roughly $200 of raw material to every new car sold each year for a grand total of $25bn. That’s roughly 1/2 a Circle (recent stablecoin IPO), 1/4 of a Microstrategy, or 1/3 of Chipotle the restaurant chain. I love a burrito as much as the next man, but I know which is more useful to the global economy!

Valterra is by far the largest of the PGM miners with 30% of global reserves, twice its closest peer and is consistently the most profitable. However, there are two other South African based companies that round out the PGM oligopoly, Sibanye Stillwater and Impala.

Sibanye has been poorly run and as a result is significantly levered, as well as being diversified across several commodities so not a pure play on PGMs. They chased lithium right at the peak of the cycle in that metal for example and will shortly open a lithium mine into an oversupplied market with declining prices. More recently they’ve been touting their uranium credentials because that mineral is currently in vogue.

The other main PGM miner, Impala, has a significantly inferior safety track record, having tragically suffered 26 fatalities in the past 3 years (Valterra has suffered 3 over the same period). I don’t want to trivialize this and of course any deaths is too many. But the reality is that all industrial activity is dangerous to some extent – 2 people were killed in the US last year installing rooftop solar for example. Valterra has worked hard and made enormous strides in improving miner safety, particularly given the historic context of the worst days of Apartheid when (predominantly black) miners were often viewed as expendable. The company’s largest mine is an open pit operation which is inherently less risky than deep mines which in some cases are several miles under the ground.

But arguably the most interesting aspect of Valterra is the possibility of uneconomic actors. In his classic investing book, “You can be a Stock Market Genius” Joel Greenblatt described how a key source of mispriced opportunities is when ‘uneconomic actors’ sell a stock for reasons unrelated to the company’s underlying value.

A prime example he cites is spin-offs. On June 3rd Anglo American spun off a little over 50% of the shares of Valterra to its shareholders. What this means is that lets say you run a mutual fund with a 1% position in Anglo American, with a diversified exposure to copper, iron ore, diamonds as well as PGMs. As of June 3rd by my calculations you now also have a roughly 0.2% position in pure play PGM miner Valterra.

Many of these fund managers will have all kinds of constraints in terms of company size, index inclusion, country of operations, minimum position size etc that they are permitted to hold within a fund and thus in some cases will be forced to sell.

Many spin offs have limited historic financial information. While that is not the case here, since Valterra has long had an independent listing, it often takes time for new shareholders to research the company and make a decision to buy.

Anglo American retains a 20% stake in Valterra which it is obliged to hold for at least 90 days, so there may well be another ‘uneconomic seller’ event. Most likely Anglo will sell this stake into the market rather than spin it out.

It is worth noting that Anglo’s timing is, shall we say, unblemished by success. Greatest ‘hits’ include a multibillion dollar Brazilian iron ore acquisition right at the top of the market just 4 weeks before the Lehman collapse and conversely spinning off their thermal coal assets right at the bottom of the market in early 2021 (that stock would then 12x in just over a year). Even the spin off of Anglogold in 1998 pretty much bottom ticked the 40+ year low in the gold price. So you might regard Anglo American’s decision to sell off Valterra as a bullish signal.

With the (partial) exit of Anglo there will be no controlling shareholder, with the Public Investment Corporation (basically the SA government employees fund) the next largest owner with 11%. The board and management are heavily populated by ex Anglo American executives (one, Dorian Emmett, joined in 1975 when it was still called JCI!). Given my earlier comments this may not sound like a glowing endorsement but the platinum business at least has been very well run, focusing on high quality, low cost assets, disposing of the inverse, improving safety and avoiding acquisitions and diworsification into overseas adventures. Management comments and actions suggest they aren’t interested in deal making, even with the freedom of a post Anglo-controlled world. Emmett, who has been Chair of Amplats’ Safety & Sustainable Development Committee since 2009 was a senior exec of the platinum division from 1996-2004 so will have a keen appreciation of the PGM cycle.

Digging up the Past and Rolling Forward

You can see from the below that the numbers are all over the place, particularly the further you go down the income statement, as the business is buffeted around by fluctuating commodity prices. Sales are the same as 2006, and profits far lower indicating this is not a buy and hold forever investment.

In recent years the company has been net cash, nice evidence of conservatism. Anglo American paid out a big dividend pre-spinout so the business presently has $600m of net debt, about a year’s worth of profit at current platinum prices.

It’s not clear what the dividend policy will be going forward but in recent years they’ve been paying out roughly half of profits.

Risks

While this is a company that I have recently bought, it is definitely at the riskier end of investments I would recommend.

Firstly substantially all the assets are in South Africa, an emerging market, where mainstream politicians have regularly called for the nationalization of assets to address inequality. I don’t think this is a realistic likelihood but it is clearly a risk worth noting. South Africa does have very advanced, independent legal and political institutions. But the dominant ANC (African National Congress) – Mandela’s party which has since increasingly been pervaded by corruption – lost its majority in government in 2024, making it arguably more beholden to extremist elements going forward.

Secondly it’s a commodity producer. By definition they have no control over the product they’re selling. PGM prices can and do trade below cash costs of mining the metals. Valterra has the advantage of being the largest miner with the lowest costs per ounce of metal mined. So if they’re losing money, the industry as a whole will certainly be suffering, leading eventually to mine closures and falling production. But the emphasis needs to be placed on eventually as this process can take years to play out.

A global or regional economic recession typically leads to declining new car sales, sapping demand for catalytic converters which could lead to oversupply and declining PGM prices.

Finally I am always conscious that being long commodity prices is betting against technological innovation, which in the arc of history is a losing bet. Any number of advances would see the PGM prices fall, from technologies that make the metals easier to find and extract, to improvements in battery technologies and even advances in autonomous vehicles (in theory if we have a car at our beck and call we don’t need one of our own sitting idle on the driveway). I would note that Jevons Paradox shows that the more efficiently we use resources the more we tend to use of them, so we won’t necessarily use fewer PGMs in future, but history shows they will be priced lower in real terms.

There is no specific currency risk here as metals are priced and sold in $. To the extent that the South African Rand depreciates that is a tailwind to the company as many of their costs (principally labor) are in Rand. In the long run however labor will expect to maintain their purchasing power in real terms so currency depreciation will be reflected in Rand wage growth. Labor in South Africa is typically unionized.

Conclusion

Commodity companies are notoriously difficult to value given the cyclicality of their profits & cashflows. The last thing you want to do is pay a low multiple of profits because this normally only tells you that we’re at the peak of the cycle.

One can try to calculate replacement cost, i.e. the cost to replicate their tangible assets, which is difficult given the idiosyncrasies of different mine economics, not to mention the fact that so few new platinum mines are being built today.

However a crude approximation is to use P/B, i.e. the market cap of the company divided by its book value (Valterra has no intangibles so no adjustment is required). The company currently trades at 2.3x which compares against a 10 year average of 3.2x and 3.9x over 20 years. The stock did trade as low as 1.3x as recently as 2024 and 0.8x back in 2015 so we are not getting in at the absolute bottom, but nor are we near the cycle peak. Below 2.1x P/B would put the stock in the bottom valuation quartile over the past 20 years.

I also like to think of commodity equities as similar to a (perpetual) option. While it is virtually impossible to predict when they might happen, parabolic price spikes in commodity prices do occur fairly regularly. Traditional options have an expiry date, and so if you’re betting on a price spike, you’re highly likely to lose all your money to time decay. By contrast commodity equities (when they are not highly levered) do not have an expiry date. It is hard – for me anyway – to price that optionality, but I find it to be quite valuable.

So in Valterra you have the best quality miner, just outside the bottom quartile of valuation range in a sector experiencing declining supply and demand likely to exceed on the upside. A risky Buy.

Disclaimer

This article is purely for informational and entertainment purposes and should not be construed as investment advice. Please consult a financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Please also assume that I own and intend to trade any stocks discussed before and after dissemination of this report.

AngloAmerican looks great itself - only reason not closer to trough p/bv is that think has writen off the goodwill sold to it those canny Oppenheimers for De Beers. Dressing oneself up for sale at request of BHP quite a strange management philosophy

Bullish on PGM