TGS

The treasure map company!

A trade war with China, a kinetic war in the Middle East, the threat of another in Venezuela. Government largesse, government shutdown. It often seems that nothing can prick this bull market.

Perhaps the only thing that can stop the market in its tracks is an energy price spike. If economic activity is energy transformed, as Louis-Vincent Gave is fond of saying, I like to think of the oil price as akin to a real interest rate, one that cannot be manipulated by central banks. When oil prices rise, the cost of virtually all economic activity also rises, acting as a depressant.

Spiking oil prices were a coincident factor contributing to both the 2001 and 2008 recessions.

I suspect that President Trump intuitively understands this. Much of his foreign policy can be viewed through the lens of trying to get energy prices down – from orchestrating a peace in the Middle East, pushing for regime change in Venezuela (which possesses the world’s largest oil reserves), propping up Milei in Argentina (where the Vaca Muerta is one of the world’s most prospective shale gas assets) – all may be geared towards getting production up and prices down.

And inadvertently or not, Trump has gotten his way, with WTI sitting below $60, the lowest level in almost 5 years. So that makes it – in my opinion - a reasonable time to hedge against the risk of an oil price spike. To be clear, that is not my forecast – I am not a subscriber to a Peak Oil thesis, principally because I’m bullish on human ingenuity. However, it is optimal to buy insurance when it is cheap, when the risk appears remote, not after the fire is already on the horizon and fast approaching.

And you can see in the chart below that the market is basically predicting flat oil prices out a decade:

TGS

Ok so if now might be a decent time to hedge against an energy price spike, there are many ways to express this. You can have a barrel of oil delivered to your house (not advised!), buy the physical via a derivative or take your pick of oil related equities.

I like the latter because with the right stock selection you can hold a perpetual option and get paid for the privilege. Moreover, while most companies in the oil & gas sector are low quality price-takers, the company I am profiling is a high return, cash generative business with unique assets.

TGS is in their words, “a leading global provider of multi-client seismic data and associated products to the oil & gas industry” or in my words, TGS is in the business of making treasure maps!

In most of the world, and particularly offshore, the sub-surface is owned by the government. At the beginning of the process of drilling for oil, the respective government will auction off prospective acreage to oil firms. In advance of these auctions bidders want to know what the geology of the area looks like, but it can be expensive, not to mention time-consuming for an individual firm to conduct extensive underground surveys.

TGS and other seismic mappers will approach these interested parties who will band together and pre-fund the exploration work in exchange for a discount on the results TGS obtains. This creates for mappers a business with scale benefits and an attractive cash flow profile.

Hence over the years TGS has built a very extensive library of 6.3m line Km of 2D maps, and 3.1m square Km of 3D seismology at a cost of over $6bn.

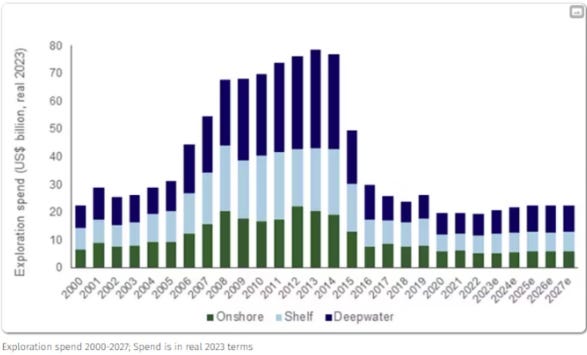

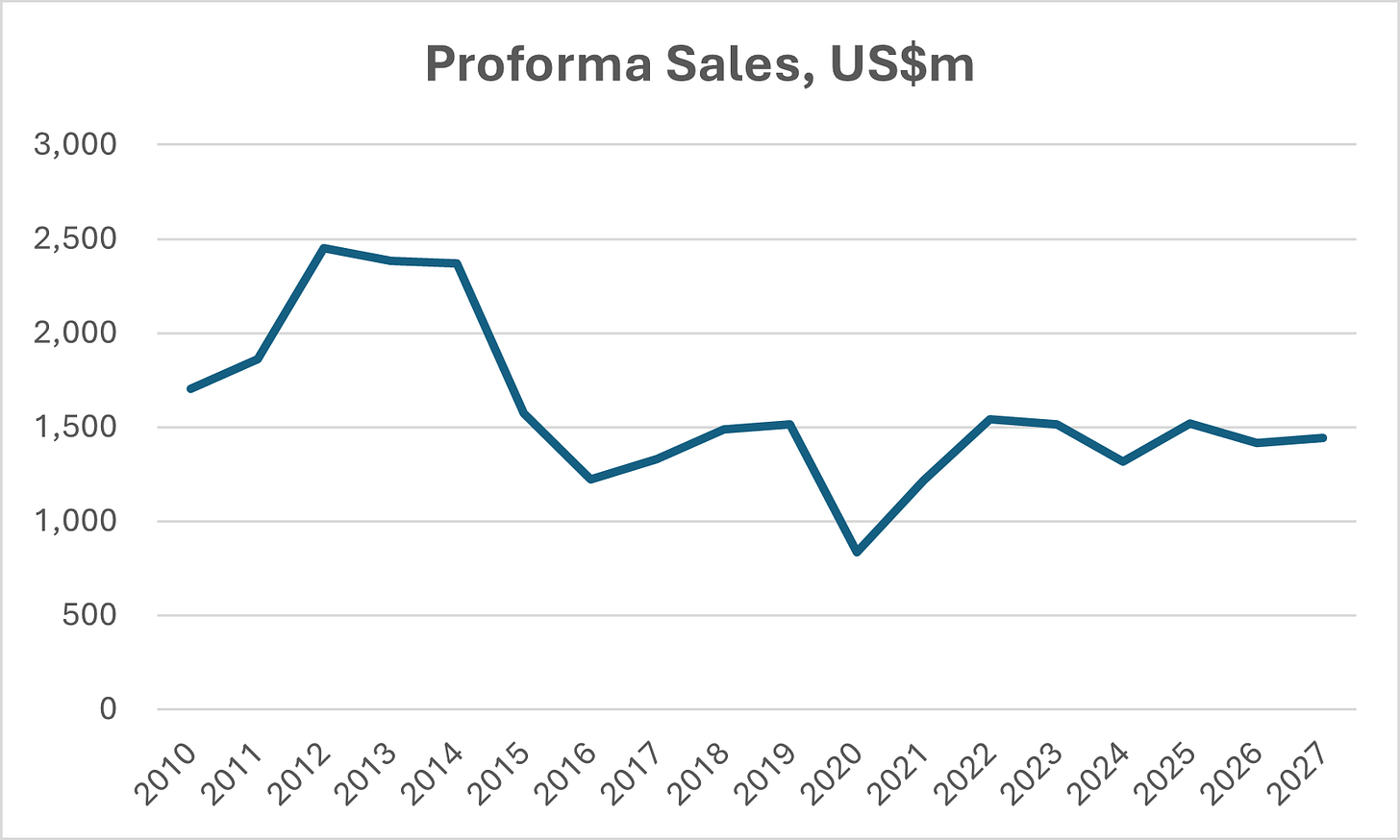

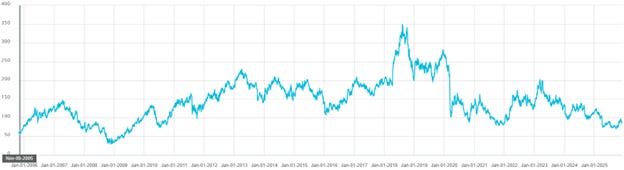

As you can imagine (and indeed see in the chart above) exploration for oil & gas is highly cyclical. When prices are high producers are flush with cash and keen to invest and grow, whereas when prices are low cash needs to be conserved and the economics of seeking out new discoveries are not as attractive. Save for a brief period following the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022 this has been a fairly miserable decade for oil companies. This weak price environment has also been exacerbated by hostile regulation and doubts over the longevity of oil demand, acting to discourage exploration.

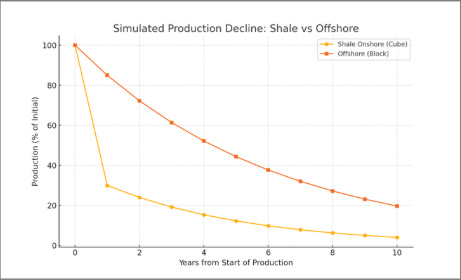

So you have a cyclical industry (oil & gas), within which exploration is the most cyclical area. And even within exploration, offshore is viewed as the long end of the whip. This is because offshore reservoirs tend to be much larger and slower burning (low decline rate) with a greater proportion of production in the out years, whereas shale, which has been the main production growth area over the past decade, is more characterized by a short sharp burst of production. Hence exploring and putting into production offshore oil & gas requires a higher degree of confidence in the long term price outlook, a confidence that has been in short supply for much of the past decade.

I should note, TGS is not purely exposed to offshore. They haven’t disclosed the segment breakdown more recently but in 2019 onshore North American seismic work was 13% of total, and likely higher today. But clearly offshore seismic work is the lion’s share of the company’s business.

The silver lining of this challenged environment is that it has forced consolidation of the mapping industry. Many players have exited the business through bankruptcy and others have pulled out due to poor returns including Schlumberger and Viridien (who sold their vessels). TGS has also played its part in the consolidation, acquiring PGS in 2024 (as well as a seismic library from a bankrupt peer).

That leaves only two companies with the full suite of seismic mapping capabilities, TGS, and Shearwater which isn’t public but is a high yield issuer so publishes financials.

So this appears to be a very attractive point in the capital cycle: low returns have caused capital to exit the sector enabling the pie to be split among the survivors. A lower denominator in time leads to improved returns on capital, eventually leading to more capital investment and the cycle repeats.

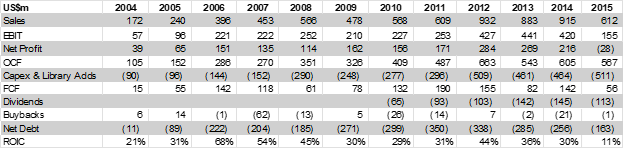

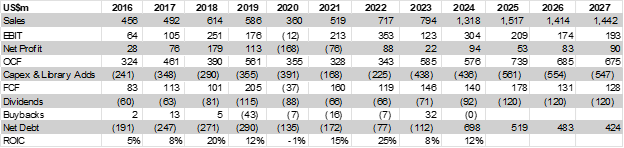

To exemplify where we are in the cycle, here are the financials for TGS:

There are few key things to note from the above. Firstly there are two distinct periods, pre the oil price collapse of 2014 when ROIC averaged 38%, and the last decade when returns have been much more challenged, averaging 11%. That said there is only 1 loss-making year in their history (2020).

Secondly, the group has been substantially net cash for its entire history (and in spite of a tough decade) up until the acquisition of PGS consummated in 2024. This rolled over pre-existing debt that PGS carried and is somewhat expensive (8.5%). TGS is committed to paying this down through cashflows, and has already begun paying debt down, with a target of $250-350m.

Third you can see the very substantial investment in seismic library assets. I have lumped it in with capex, but this line is almost all capitalized costs of adding new seismic data. Again this investment is mostly pre-funded by clients so is low risk - the company has over $500m of deferred revenue, i.e. upfront payments from customers on its balance sheet.

History

Following the second oil price shock of 1979, Tomlinson Geophysical Services (TGS) was founded in 1981 in Houston, Texas to map the Gulf of Mexico. That same year on the other side of the world, NOPEC (Norwegian Petroleum Exploration Consultants) began mapping the North Sea.

The contract seismic business (collecting seismic maps for a single client) was by this point well-established but TGS & Nopec were, independently, the first companies to establish the multi-client business model, which made mapping substantially cheaper (10x) for oil companies and improved the economics for seismic firms.

Another Norwegian seismic mapping firm PGS (Petroleum Geo-Services) was founded in 1991. Soon after TGS & PGS formed a joint venture to enter the Gulf of Mexico market with new 3D mapping technology.

TGS & Nopec merged in 1998, combining their respective expertise in the Gulf of Mexico and the North Sea, and making Oslo the headquarters for the combined entity.

As you can see in the Wood Mackenzie chart above, the industry enjoyed a boom in the 2010s as high prices compelled oil companies to go out and spend on exploration, followed by a prolonged bear market from 2014.

Business Model

The bulk of TGS’s balance sheet historically has been the seismic library. The firm amortizes this asset over 4 years. This however is a maximum and typically the amortization is faster than this, i.e. the company is more conservative than the stated policy. In reality of course the asset is not consumed, it remains on a hard drive somewhere, and there are occasions where this data becomes commercially useful long after it has been fully amortized (due to new data analysis techniques, not to mention new oil & gas extraction techniques, which opens up previously discarded reserves). TGS is free to sell this data again and again to all-comers. The company has $6.4bn of capitalized seismic data, almost entirely amortized ($5.9bn).

There are clear scale benefits in this business, one needs the capital, technical capabilities, equipment and credibility to move quickly and convince clients to pay up to have surveys conducted. Once the first mover has begun mapping it doesn’t make a lot of sense for a competitor to cover the same tracks. This is clearly advantageous to TGS, who also have lots of industry leading analytical tools:

By contrast, in the offshore drilling rig business, a favorite of investors trying to call the turn in offshore capex, there is virtually zero differentiation between companies, so it is a competitive fight over day rate pricing.

And on the subject of drilling rigs, those are extremely expensive pieces of kit. Day rates are on the order of $500k a day. If an E&P company is going to commission a rig they want to have the best possible data to inform their investment decision. In other words, the seismic mapping and analysis is a very small part of the overall cost but critical to the success or otherwise of drilling activity.

“Assets weren’t assets, assets were liabilities” Bob Robotti

The other major ‘asset’ in this industry is the vessels & seismic equipment required to carry out the mapping activity. I put asset in inverted commas because, as esteemed value investor Bob Robotti points out, if you own big pieces of kit at the wrong point in the cycle and you can’t command rates that cover your costs, they are more of a liability than an asset.

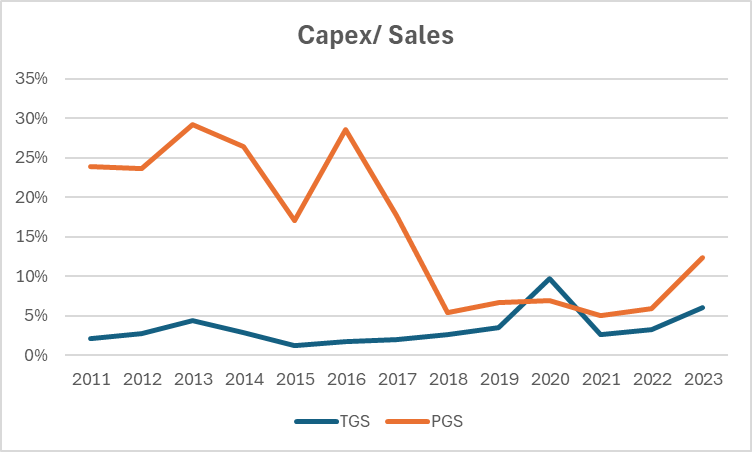

This is actually how TGS came to own PGS. PGS was the larger of the two companies historically but got into trouble due to excessive leverage taken on to fund ill-timed investments in vessels ordered right at the top of the cycle, clearly evidenced below:

The top spec vessels cost PGS around $250m each between 2013 & 2017. They had 6 of these. TGS was loath to let PGS wither on the vine, lest those vessels get into the hands of a new entrant via takeover or the bankruptcy courts, just as the cycle turned. TGS got the business, inclusive of debt for around $1.4bn even before ascribing any value to the muti-client library valued on the books at over $400m.

As you can deduce from the chart above, TGS historically had a very different approach to vessel ownership. From the 2022 annual report (prior to the acquisition) “TGS did not own or operate vessels or seismic equipment.” They go on to explain the advantage of this strategy: “we only access these resources when needed and are free to use the most appropriate vendors and technologies to tackle specific imaging and intelligence challenges.” Instead of ownership, TGS historically signed vessels on short to medium term leases, or engaged in what they call ‘joint operations’ which is basically where they convince the vessel owner to give them free use in exchange for a revenue share on the seismic mapping that TGS carries out. Again the upfront payments from oil companies are useful because it provides a guarantee backing these revenues.

The combined entity has already been taking action to reduce its asset intensity, announcing a decision in June to sell off two older (from the late 90s) vessels, as well as stacking (basically putting in storage) another to reduce costs. Rather than a quarter billion dollars, these vessels will reportedly be auctioned off for less than $10m a piece, which is presumably their scrap value. Per the CEO the company is “sending a message to the overall market that we are going to be disciplined”.

After these disposals TGS will still have a state of the art modern fleet of vessels valued at $840m net of depreciation. This cuts both ways, if the cycle fails to turn the firm is stuck with higher fixed costs, notably the cost of debt service, but asset ownership also allows the company to capture more of the upside if exploration activity does pick up. The problem with leasing in a bull market is that renewal rates tend to go up as assets become scarce.

Ownership

Typically I avoid companies without any clear owner, particularly in cyclical industries, as there is little check on the incentives for management teams to pursue value maximizing (for themselves) decisions, which often leads to very pro-cyclical behavior. Cyclical businesses, by their nature, generate lots of capital in times of feast. Whereas the best thing for shareholders might be to return this capital in the form of dividends, this leaves a much smaller company per whatever your preferred metric. Empirically, larger companies pay their CEOs more. Not to mention that it is a lot more fun to commission a large factory, headquarters or vessel. I’ll offer a free subscription for life to any reader who can find me a ribbon cutting ceremony for a billion dollar buyback!

In this case we don’t ostensibly have a clear owner. The largest shareholder with 8% is the Norwegian social security fund. This is a passive position and similar in proportion to the fund’s holdings in other listed Norwegian firms.

However, you can see from the company’s history that it has been run in a very counter-cyclical and conservative fashion. I suspect this might be related to the fact that the firm has had just 3 CEOs since 1995. Indeed that CEO from 1995, Hank Hamilton, was Chairman and a material shareholder of the company up until his retirement in 2022. So there is a high degree of continuity and longevity, which hopefully influences decision making.

Current CEO Kristian Johansen has been in charge since March 2016 so is coming up on a decade of tenure, and was CFO for 6 years prior to that. The CFO has also been around for a decade. Indeed even the Chairman of competitor Shearwater is Johansen’s predecessor as CEO of TGS, so perhaps this improves the likelihood of the industry acting rationally.

The Future

I’m not going to devote much time to the debate over whether we will be consuming hydrocarbons in 10 or 15 years’ time. The evidence to date is that despite trillions of dollars of investments in renewables, the vast majority of the world’s primary energy production continues to come from hydrocarbons, 81% in 2024, down from 86% a decade prior (per the Statistical Review of World Energy). This is a figure that excludes all kinds of uses for oil & gas in petrochemicals, which are of course everywhere in our modern world.

The reason I’m not going to delve down that rabbit hole is that this line of thinking misses the point I am arguing. Which is that if the price of oil spikes, how will the rest of your portfolio do? Indeed what will happen to the cost of your daily basket of food, the cost of heating your home, of filling up your car and of the products Amazon ships for you from China.

My guess is that the answer is, down, in the case of your portfolio, and up in the case of everything else.

I tend to think of these kinds of investments less as a directional call on oil prices and more as a hedge against future spending. By that logic, if the S&P500’s sub-3% weighting to the Energy sector is indicative, most people are very much under-invested in energy, assuming they intend to fly on a plane or replace the tires on their electric car.

I should also note that faced with a brutal downturn, in addition to buying up distressed competitors and assets, TGS has also sought to pivot somewhat into adjacent areas. So in addition to oil & gas related seismic data collection and analysis, the company is also selling its wares to for example companies interested in doing underground carbon capture & storage. They have via M&A entered the business of data analysis software for offshore wind turbines as well as real-time data management for solar & offshore oil & gas projects. Collectively ‘New Energy’ add up to 5% of sales.

More significantly another acquisition made them the leader in ocean bed nodes which are helpful to producing wells as opposed to exploration. This business was 18% of sales in 2024.

“Invert, always invert” Charlie Munger

Rather than trying to predict the future, an inherently fraught exercise, I prefer to ask the following question: how can I invest in a company where the expectations for the future are low, leaving scope for the business, or indeed industry, to jump over that one foot hurdle and exceed these forecasts?

In the case of TGS, the consensus expectations are very modest, with 2027 sales of $1.4bn, 5% below this year. On a pro-forma basis (i.e. pretending that TGS&PGS were one combined entity historically) that is basically in line with what they’ve done each year in the past decade of the down cycle, save for 2020.

So the expectation is that the company muddles along, despite a vastly consolidated industry. If oil prices do rise significantly TGS will do far better than this. Importantly, the cost of carry here is significantly negative as one collects a 7% dividend yield which is well-covered by free cashflow.

Risks

This is quite a risky investment in the sense that one of the company’s key variables (the oil price) is completely out of their control. I think this risk is somewhat mitigated by the timing, with oil prices below $60. This stock likely won’t perform well if the oil price falls to $40, but again many of the other things in your portfolio will most likely go up as energy represents a material cost to most businesses and indeed consumers.

The business has more debt than I’d like, but the management team is committed to reducing this. The company refinanced its debt at the time of the PGS acquisition out to 2030 so they have no imminent maturities. Even in this tough environment, due to the nature of the business model, the company remains highly cashflow generative so I don’t anticipate any issues here.

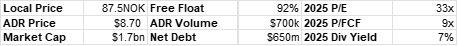

In terms of currency, the business operates and reports in US$. There is a local line of stock, priced in Norwegian Krone, as well as an ADR, which is pretty liquid ($700k) a day and of course is priced in US$.

Conclusion

I think this stock warrants a position in a portfolio as a cheaply priced perpetual option which you are paid to hold. BUY.

Disclaimer

This article is purely for informational and entertainment purposes and should not be construed as investment advice. Please consult a financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Please also assume that I own and intend to trade any stocks discussed before and after dissemination of this report.

Can also buy VIRI FP. Same but no ships.

Do have a position in tgs and also in fugro n v

Believe they both are cheap and i m maybe a little bit early but dividends are ok and debt ratios are acceptable.